Cozumel Diving: Do Marine Animals Mate for Life?

In the spirit of Valentine’s Day, this post by combines some Cozumel diving pictures with an eye toward love – namely a love of the ocean and an investigation of what animals mate for life.

Or I guess you could say I looked for what we as humans might often assume to be loving behavior when scuba diving and observing some cozy couples among the incredible marine life here in the Caribbean.

Next to the annual Carnaval festivities, Saint Valentine’s Day is the next upbeat holiday on the dance card if you are visiting Cozumel in February.

Cozumel Island with her celebrated marine park is not only a world-class diving destination but was one of the first “Hope Spots” for the world’s oceans, established by Sylvia Earle’s famous “Mission Blue” project, that stemmed from her renowned 2009 TED Award recipient talk focused on promoting and creating more marine protected areas.

Cozumel’s superb year-round diving conditions, varied dive sites, and abundant underwater marine life will live up to that reputation.

I’ve had some extra time to look back through some of my favorite moments of aquatic marine “love” I’ve encountered along these awesome reefs.

Cozumel Marine Life: Colorful, Cute, and Carnal

Lots of

The natural environment of the mesoamerican reef is full of these shapes and textures – like the occasional heart-shaped purple sponge, and heart-shaped horseshoe worms, brilliant against their hard coral backgrounds.

And then there are the more animated animals. The more you go diving, the more you catch glimpses of the natural behaviors of various marine life.

In Cozumel, I’ve been able to take countless cute – and some downright racy – “couples” photos, where I imagine the animals as lovers or friends.

In some of these intimate images, it’s quite clear I’ve caught these marine mates in the act.

But other times I’m not so sure. Maybe they’re just siblings that grew up together, or neighbors finding their own kind. Sometimes they just seem like friends, hanging out and watching each others’ backs.

But is that even possible? Do fish and marine animals make friends? Do they feel affection or love? And in the ocean, what animals mate for life?

First off, as this series gets going, let’s address something we all do, all the time, for better or worse: anthropomorphism.

Why Do We Anthropomorphize Animals?

It’s really easy to make up cute stories of love or partnership when you see pairs of fish out swimming together in unison, or crabs embracing each other, two colorful Cozumel cleaner shrimp paired up in a cozy home, or a gang of Caribbean lobsters holed up in a club-like cave. I do it all the time! Can’t help myself.

Take these two spotted moray eels in Cozumel, below, for example.

Ever since I took these photos a while back, I can’t help thinking of them as a happy but bickering married couple, trading one-liners, or arguing over “the clicker.”

It’s in our very human nature to anthropomorphize or to ascribe human traits and feelings onto other animals or even inanimate objects. We want to know what they’re thinking and doing, so sometimes we just make it up!

Growing up on animated Disney and Pixar movies doesn’t help matters.

But as explained in this intro and video from brainfacts.org, it turns out it’s also a natural and evolutionary function of our human brains:

Our love for talking animal cartoons has an evolutionary purpose: assigning human traits to non-humans kept our ancestors wary of potential dangers. Anthropomorphism activates parts of the brain involved in social behavior and drives our emotional connection with animals and inanimate objects.

Sometimes this is a good thing, helping us feel ties to our non-human cohabitants, or sense real connection (dogs, octopus) or real danger (tiger, raccoon in the daytime). It also helps add empathy to scientific and logical efforts against deforestation, overfishing, and other climate risks.

If we can somehow relate to animals, we can also care about their fate – and ours as their Earthly neighbors.

But you can get carried away with anthropomorphism, especially where the marine environment is involved. It’s fun imagining a couple of eels bickering, or two pretty little sea slugs out for a stroll, or dancing “cheek to cheek.”

Unfortunately, the odds are that your sweet story would be inaccurate.

More likely, those two are about to go find, kill and eat something.

Or, they may just get on with it and mate (which down here underwater often looks decidedly…Un-Disney).

Do Marine Animals Socialize?

From watching movies like Blackfish and The Cove, we know that the big guys, like orcas and dolphins, form family units, exhibit sophisticated relationships and coordination and that they seem genuinely distressed when those social bonds are disrupted.

I also just found some new and on-going studies of manta ray behavior in the Raja Ampat, Indonesia region showing that they, too, form social bonds and actively choose social partners.

As a recreational scuba diver in Cozumel, diving among hundreds of species of small tropical fish and seemingly random invertebrates in all different cracks and crevasses, it’s pretty hard to decipher specific social cues and behaviors down there. Especially with no marine-bio credentials.

But you learn more and more with every dive.

If you’re into scuba, you’ll likely agree that some of the most interesting things to watch during a dive are not just the marine creatures themselves, but the interactions between them. In the dive sites of Cozumel, there are all kinds of underwater and inter-species social activities going on among the coral reef inhabitants on a daily basis.

Scuba divers here will often see angelfish following hawksbill turtles around the reefs of Dalila or Cedral, hovering over them, waiting to feed on their scraps.

There are medium-to-large-sized southern stingrays often cruising along the sandy bottom, stalking hermit crabs for their next crustacean meal.

If you’re lucky, you might even spot a green moray eel swimming out of its hiding spot, and actually working in coordination with a large grouper to hunt smaller prey.

Everywhere you look while diving in Cozumel, you can find various critters battling over turf, tidying their nests, eating and pooping, laying and protecting their eggs, and of course – mating and reproducing.

This, btw, is one of those where I’m quite sure active mating is going on.

According to one of the more informative summaries I found here, from Lamar University, flamingo tongue sea snails are “dioecious” meaning they are either male or female and remain so as adults. In this image, note the distinct, white tube of the male (lower right) inserted into the female’s shell (upper center). (Each of these snails are approximately 1”/3cm in length)

Marine Species Pair Bonding: Is It Love or Longevity?

OK, so we’ve seen some obvious mating moments. But what about the same-species interactions that last longer, and aren’t obviously tied to mating or offspring?

Sometimes when scuba diving in Cozumel, you’ll see two of the same species traveling around together. Again, if you let yourself imagine you’re in a Pixar movie, they may look like a cute “loving” couple, or at least a couple of dive buddies, heading out for a beer.

This could be a coincidence, or it could be something more.

Based on the common body of knowledge out there, there are only a few species known to form true, long-lasting “pair bonds” in the ocean.

Luckily we have a few of those that are common to the Cozumel diving scene, so now you can bet I’m paying even more attention.

The three main “pair bond” species I’m referring to are:

- French Angelfish (Pomacanthus paru)

- Butterflyfish (Chaetodon) **the “Foureye Butterflyfish” is our featured coloring book page in this month’s newsletter..hint hint

- Banded Cleaner Shrimp (Stenopus hispidus)

Sidenote on Biological Monogamy

The question (or assumption) comes up often about whether or not these animals are monogamous. At least in terms of how we understand the term monogamy as human animals (who buy Valentine’s Day cards and bouquets of flowers…).

From what I’ve learned, recognized monogamous relationships in any animal species are rare. Even when they are found, they are considered either “social” (not necessarily exclusive, usually temporary, for one or more breeding seasons/cycles) or “genetic” (extremely rare, and still may be temporary).

Biologists often refer to “monogamous mating” even when these pair bonds stick together only for a relatively short time. If I understand this all correctly, only true “genetic monogamy” implies the two animals form a long-lasting and sometimes exclusive pair bond, which can be proven by the study of their genetic offspring.

So here’s where our anthropomorphism has to be checked at the door.

The genetic monogamy listed above may be the only example of what we humans think of as a long-term, monogamous relationship. And examples of that are the most common (but still extremely rare, if even proven!) in bird species.

And even then, according to a not specifically footnoted but credible-sounding statement on Wikipedia, “no one species has been identified as fully genetically monogamous.”

Common Cozumel Pair-Bonding Marine Species

So, back to basic pair bonds in the marine world, and a reminder of the three most commonly observed pair-bonding species we can see while diving in Cozumel:

- French Angelfish (Pomacanthus paru)

- Butterflyfish (Chaetodon)

- Banded Cleaner Shrimp (Stenopus hispidus)

French Angelfish Pair Bonds

The first very common “pair bond” you’ll find in Cozumel – and that at least one (admittedly old) university study says is indeed “monogamous” – is between two adult French Angelfish, as seen below:

Angelfish frequent Cozumel’s National Marine Park, and the types you’ll find here are usually of the French, Grey, and Queen varieties.

In marine biology literature, the adult French angelfish (Pomacanthus paru) shown above (about 11”/28cm tip to tail) are the variety that most often gets cited as monogamous.

Like most pair bonds, what ties them together is a sensed strength in each other as viable producers of offspring and defenders of their territory for food procurement and general survival.

According to this article about long-term pair bonding in the Smithsonian Magazine:

Typically in pairs, French angelfish (Pomacanthus paru) help each other defend their territory against other fish. The couples have been observed spending extended periods of time together, exhibiting more of a monogamous social structure. Genetic monogamy (i.e. testing fertilized eggs to confirm they come from a single father) hasn’t been confirmed, but there have been observations of pairs traveling to the water’s surface to release their eggs and sperm together.

Caribbean Butterflyfish and Pair-Bonding

Our next cute couple that always swims around in a pair is the butterflyfish. Here is an underwater shot from Cozumel of a pair of spotfin butterflyfish (Chaetodon ocellatus). These two are around 4”/10cm from tip to tail, and so named because of the tiny black spot on the top rear of their dorsal fins:

The butterflyfish family comes in several pretty varieties, and are all known for the tendency to pair bond.

Probably the most common to see when you’re diving in Cozumel, and my personal favorite, is the foureye butterflyfish (Chaetodon capistratus), shown below:

Rest assured, if you watched this adorable little (4”/10cm) foureye butterflyfish swim around for a few moments, you would see it locate and reunite with its “mate.”

They frequently stray apart and nibble on various corals in the vicinity, but almost always reunite within a minute or two.

In fact, a scientific study abstract posted here on nature.com indicated that as “corallivorous” fish (I learned a new word!), their pair-bonding also helps each other ward off competition, and gain more “bites” of coral in a given span of time, obviously boosting their overall food intake.

The abstract of this study also adds an interesting note on that pesky “anthro” question of monogamy:

Although pair-bonding butterflyfishes are presumed to have very high levels of partner fidelity (up to 7 yrs) the ecological basis of pair bond fidelity among these organisms remains unknown.

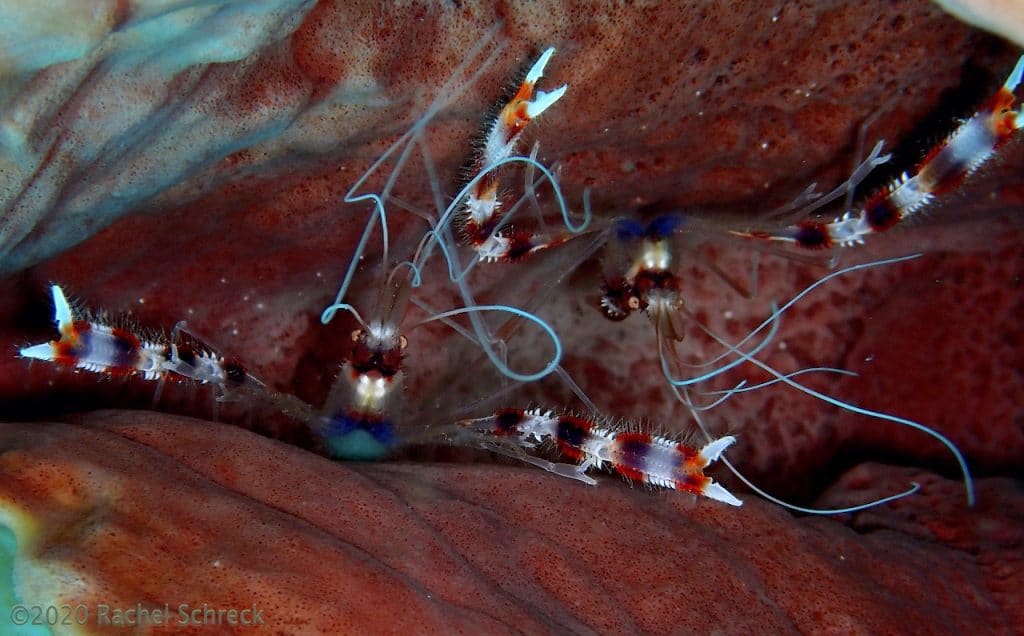

Banded Coral Shrimp Sometimes Mate for Life

The awesome and humble banded coral shrimp, a.k.a. banded cleaner shrimp (Stenopus hispidus):

These critters are some of my favorites, and partly because they are easy to find. As a newer diver, it was a big thrill to start finding macro life, and these banded cleaner shrimp are seemingly everywhere along the reef.

They are also pretty brave, so as an underwater photographer, they’re a great practice subject.

They do hide though, usually in and under the base of the coral reef foundation, or within the safe walls of barrel and vase sponges. As you learn more, you can spot them by their “tell” – leaving their long, white antennae exposed, protruding out from their hiding spot.

This may seem like a careless oversight, at first (if we’re anthropomorphizing…), but it’s really so that their antennae will sense or attract passing fish, who will then stop in for a “cleaning” session.

In general, cleaner shrimp feed off of the algae, parasites, and other nuisances of larger fish/turtles/anemone/bigger organisms. So while they need to protect themselves from being eaten by predators, they also need to be found by their symbiotic partners sometimes, in order to get a decent meal.

The banded cleaner shrimp have small and delicate-looking central bodies, called the “carapace,” that’s usually only about 1 inch/2-3cm long, though can ultimately grow to double that size.

Their striped arms are relatively much thicker and longer (the ones pictured above, for example, have arms that are about 2-3”/6cm long), and their white antennae are even longer, still.

Oddly, my effort here to kinda, sorta relate all this back to human Valentine’s Day might have worked out the best in the form of this buggy little shrimp.

In terms of monogamy, some studies indicate that these banded coral shrimp have proven to be some of the most attuned, especially among invertebrates, to find and permanently bond with their one, unique mate. Sometimes for life.

Also, according to a synopsis by the Dutch Caribbean Nature Alliance, the banded coral shrimp are basically monogamous homebodies – even in the anthropomorphic version:

Two things you might not know about this little creature is that first of all, it is very faithful. A trait mostly associated with mammals and some birds, this little crustacean also chooses its mate to pair for a lifetime. The other thing is that they’re very territorial and being as small as they are, this means that their territories can’t be that big. So when you plan your holidays on the same tropical island two years in a row, you will have a big chance of finding the exact same Banded Coral Shrimp (or its mate) within a metre from where you saw it last year.

(For more on other types of cleaner shrimp in Cozumel, check out this post next!)

Well, there you have it.

Maybe there are no candlelit dinners and boxes of chocolates going on for Valentine’s Day on the coral reefs of Cozumel.

But there’s definitely courting, mating, fighting, cooperating, and some well-established pair bonds helping each other make a shelter, find food, and tell all the enemies to back off.

Sounds pretty romantic to me.

Research and Resources for Cozumel Amateur Marine Biology

I’ll joke a lot here about my new vocation as an “armchair marine biologist” and it is true. The more I see down there, the more curious I get, and the more I want to search around to know what I’m looking at.

If you’re interested in some reference books for your diving library or looking for a great gift for a scuba diver in your life, consider investing in some Caribbean reef ID books – hours of fun.

-

$32.48Buy Now

$32.48Buy NowLearn those critters!

We may earn a commission if you make a purchase, at no additional cost to you.

03/09/2024 12:34 am GMT -

$31.52Buy Now

$31.52Buy NowLearn more about Cozumel's fish - including sharks, rays, and eels

We may earn a commission if you make a purchase, at no additional cost to you.

03/09/2024 02:17 am GMT -

Buy Now$29.26

Buy Now$29.26We may earn a commission if you make a purchase, at no additional cost to you.

03/09/2024 03:04 am GMT

CozInfo’s Cozumel Packing Essentials:

|

3.5

|

3.5

|

3.5

|

3.5

|

|

$19.99

|

$249.00

|

$59.95

|

$22.99

|